I ended up designing my own training methods, based on what I learned from my talented instructors and through the observation of my own mental habits, by paying attention to what I do efficiently and how I do it.

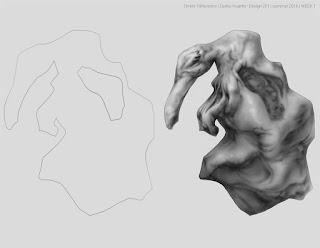

I will introduce diagrams and pictures when I find more time. Right now, here's an outline.

Biggest art myth:

Draw a lot, draw whatever you like and you will become a great artist.

Theoretically that is correct. Practically this advice is no different than saying:

Count everything, look at everything around you and try to express it through math. With enough practice you will become an amazing mathematician.

Obviously, this is not how things work in the real world. For the majority of people interested in doing art, following this advice is the surest way to quite out of sheer frustration.

Learning art consists of 2 main parts:

1. Learning as much as we can about the world around us (anatomy, perspective, optics, principles of design and aesthetics, mechanics, etc.). This you learn from books and lectures.

2. Practicing the physical and mental skills involved in art-making.

Information on the former is readily available all over the internet in a multitude of forms.

Information on the latter is hard to come by. I do not come from an artistic family, nor did I have ready access to art mentors until recently. I spent years on my own struggling, testing and verifying practical methods of efficient study of art-making. I feel it might help someone if I share what I learned.

Here are some axioms which can be helpful to absorb:

1. We cannot draw or paint what we don't know, i.e. see in our mind's eye

2. We learn by copying the behavior of those who are more skilled (we learned to speak by listening to the people around us, we learned in school by following our teachers, we learned specialized things by analyzing and studying how the masters of those specialized fields arrived at their results)

3.We get better only through repetition and regular challenges (reduced time to complete a task, unusually high quality standards, assignments involving new or infrequently used knowledge and skills, etc)

It follows that:

1. We can't expect to be able to draw something complex or unusual (human body, poses, animals, patterns, complex machinery and architecture, nature, landscapes, etc) without hours of studying and practice.

2. We cannot create "original" art from scratch without hours of tracing, copying and studying existing art (paintings, drawings, photographs).

3. We cannot get worse by practicing. The reason we sometimes feel we are doing worse today than we did yesterday, is because our minds are able to become more attuned to the subtleties of the subject faster than our muscles can express our new found understanding. What we can imagine is not always what our muscles can instantly follow.

4. Thinking we can do something and doing something is not the same thing. The former is fantasy and it is easy, the latter is reality and it is hard.

5. No matter what we are taught or how we are instructed to practice, we can only paint and draw what we see and understand. There is no better way to learn to do art, than by doing art without judgement or self-deprecation. You are who you are and not everyone will be happy with that. Instead of trying to please those who don't like your work, bring joy to yourself and to those who appreciate what you do by making more art that is you.

Here's my training philosophy and routine:

Physical skills account for around 70% of art-making, while 30% of art comes from our knowledge (of art-making and the subject we are trying to convey). Don't quote me on the numbers, I made them up. It feels right to me.

All physical skills are best acquired when extreme limitations are in place. Through repetition, the skill level increases and past limitations become the new normal. Working within limitations is a traumatizing experience, which is exactly why it triggers our natural adaptation mechanisms. Our new skills is nothing more than our adaptation to challenging circumstances.

Therefore, use challenges sparingly, no more than once or twice a week if you are doing short sessions, or once per session if you are practicing a full workday. You do not want your art to become constant torture. Peaks and valleys is the way to progress and maintain your sanity.

Drawing - regular training (equivalent of physical conditioning and stamina training)

Do not judge! Do not correct! Work as fast as you can, do not slow down! Produce as many copies as you can!

When you start slowing down or start judging, it means your mind and body are tired. Do not push past this point! Take a break. Rest. Then continue or start over.

Start by working in 20 to 30 minute intervals with 5 minutes of rest. Increase to 1 hour 30 minutes of drawing with 10 to 20 minutes of rest :

1. Trace or copy with grid (this is critical, do not skip this step - your muscles learn directly even if your brain tunes out)

2. Copy by observation (your muscles and mind are training to work together)

3. Sketch or doodle from imagination (your muscles and mind learn to apply everything you learned and make it your own)

Drawing - Adaptation challenges (equivalent of physical "to failure" and "interval training"):

Method 1: Make a precise copy of your chosen reference or study, as close to the source as you possibly can

Do not use grids or any other instruments. The goal is to copy with precision through observation. Now judge it. Overlay it over the original and note everything you did wrong.

Method 2: Time it! draw or paint the same thing within a given time interval, then reduce the interval, and reduce it some more. After drawing or painting within the shortest interval, start increasing the time interval. This method is based on one of the most valuable training techniques I learned from Anthony Jones.

15 min - 10 min - 5min -3 min -1 min - 30 sec - 1 min - 5 min - 10 min.

Use a kitchen timer, google timer in your browser, or the timer on your phone to keep track of the intervals.

Painting regular training:

Do everything you did for drawing but apply it in stages:

1. 2 value practice

2. 3 value practice

3. 5 value practice

4. color practice

Painting - adaptation challenges:

same as what you did with drawing, except apply it to painting with an increasing number of values (the scheme you used in painting regular training).

Before I wrap this up, I feel I should elaborate on the topic of reference. I recommend using drawings or paintings by your favorite artists, individual movie frames, photographs, etc.

Please make sure that if you are going to be showing your work to someone else or posting it on the web, always give credit to the original creator by indicating directly on your study image that it is a study after an artists, photographer or a frame from a movie. Always write the name of the artist (photographer) or the title of the movie. It's the right thing to do and it will keep you out of trouble. If you intend to sell your studies, make sure to get legal advice first. My advice only applies to private non-commercial effort.

I understand that my method might appear a bit convoluted. I'm making these notes for myself and I'm skipping a large number of nuances. If you have any questions, please contact me on Facebook or through Instagram. Search for my name or my username "Dreamrayfactory".

In closing, here is a short list of books I found most helpful in my studies:

- The Natural Way to Draw by Nicolaides

- The Practice and Science of Drawing - Harold Speed

- Everything by Bridgman

- Morpho - Michel Lauricella

- Freehand Sketching - Paul Laseau

- Watercolor Sketching - Paul Laseau

- Pen and Ink Drawing - Alphonso Dunn

- Everything by Jack Hamm

- Painting by Design - Charles Reid

- Figure Drawing for Concept Artists - Kan Muftic

- Freehand Figure Drawing for Illustrators - David H. Ross

- The Artist's Complete Guide to Drawing the Head - William L. Maughan

- Force: Dynamic Life Drawing for Animators - Mike Mattesi

- Figure Drawing Design and Invention - Michael Hampton

- Draw Naturally - Allan Kraayvanger

Here are 3 excellent books you might want to add to your collection, if you are looking for something more advanced:

1. Composition of Outdoor Painting - Edgar Payne

2. Light for Visual Artists - Richard Yot

3. Alla Prima - Richard Schmid

Hope you find this info useful and thanks for reading this wall of text :)